The Arena Theme

The arena theme is made up of a series of set pieces which either donít rely on cover at all, or rely on a much more rudimentary and haphazard form of cover. In the introductory sections of this book, I laid out the history of shooter design leading up to Half-Life. For most of that history, shooters used a style of design much closer to the modern arena style than to cover shooters. That is, the player and enemies were frequently thrown into a large room, and the enemies would slowly converge upon the playerís position. The player had to respond to these situations with lightning reflexes and constant motion. Half-Life and its multiplayer incarnations are, for the most part, not arena shooters. Still, the single-player campaign shows some of its Quake lineage through the arena theme. This theme is full of examples of hallways meant for kiting, large rooms meant for circle strafing, and lots of three-way fights that substitute crossfire-based chaos for cover.

There is not much in the way of over-arching organization within this theme. Most of the arena set pieces come after the beginning of chapter 11, and then with increasing frequency through the end of the game. Once the player reaches Xen thereís little cover, but plenty of combat, so naturally that combat has to take place in arenas. If I had to make the case for some kind of organization in the arena theme, I would say that the arenas start to get bigger in size, but only if you start measuring from the beginning of chapter 14. From that point until the climax of the game, the arenas mostly grow in size (to absurd proportions, eventually), mostly along the x and z axes, but eventually along the y-axis too. None of this is to say that the designers didnít do anything interesting in the arena theme; there are many arenas which are interesting in their own right. Two of my favorites are set pieces 11-2 and 12-10; playing those, you can see where the Halo designers got the inspiration for many of their multi-sided set pieces and level designs. Furthermore, the arena theme actually exhibits a lot of the cadence structure that was developed by Nintendo in the early 1990s. I donít think the Half-Life devs intended this, but I do think it shows another example of cadences in the wild, so to speak. Certainly, it helps to prove that the cadence structure is a natural form of organization in well-designed videogames.

As a last note, I want to say that there are many arena themes with some small amount of cover. For example, set piece 11-2 has a bunch of pillars which can shield Freeman from one angle of fire.

This is not properly cover as we saw it in the cover theme, because it doesnít offer Freeman sufficient protection. Any advantage the pillars convey is neutralized by some other angle, or the charge of an enemy from a different direction. Freeman has to move constantly, and that movement is the hallmark of the theme. This is different from the temporary cover segment, in which the player has to keep moving to new cover. In that segment, Freeman can maintain cover discipline by switching between objects; the process is predictable if the player knows what to do. In this theme, there might be an aperture to use for cover temporarily, but once the enemy advances, itís back to run-and-gun gameplay.

Half-Life is a transitional game. The designers had just invented modern cover, and so the distinction between cover and arena situations is sometimes a little murky. Usually, though, the playerís experience of arena set pieces is much different from the cover set pieces, however they may appear.

SET PIECE 3-1: Headcrab Elevator

The arena theme begins with a very simple challenge: Freeman is trapped on a slow-moving elevator as a long stream of Headcrabs descends upon him. Up until this point, the player has been able to run around enemies, avoiding them completely or tactically engaging them in advantageous settings. Now, itís impossible, and thereís no sneaking either; as the player is bound to the elevator platform. Of course, like any good early challenge, thereís barely any threat. Many of the Headcrabs will simply bounce past the platform, or jump off of it while trying to attack Freeman.

One nice thing about the descent the Headcrabs have to make is that it extends the amount of time the player can use to fire on them or dodge them. In this regard, itís a great way to teach the player about how to deal with Headcrabs generally. The designers didnít have to do anything special; they only had to rely on global physics already in place and drop Headcrabs from a greater distance to achieve this training-wheels effect. Also notice that the first arena set piece in this game also looks a lot like Space Invaders. The Headcrabs fall in a rate and pattern similar to the projectiles from the alien ships; this forces the player to move side-to-side while occasionally shooting. All that is missing is the cover.

SET PIECE 5-6: Yard Brawl

A great deal of content separates the first two set pieces in the arena theme. Almost three chapters later, the second arena set piece sees Freeman confronted by a large number of HECU troopers with relatively little usable cover. This is not to say that there isnít anything resembling cover, because thereís actually a lot of that.

The problem is that the marines are scattered about this area such that any apparent cover will instantly become useless when the marines swing around it and surround Freeman, which they are unusually likely to do in this set piece. Once the battle begins, itís going to be a stand-up/arena-style fight no matter where it takes place. Any ďcoverĒ will last only a few seconds.

Before the player obtains aggro on these troops, however, thereís an obvious and very necessary health machine on the wall. Once the player does gain the attention of the enemy, the HECU troops will charge right into the room.

Although there is something to hide behind, for an instant, itís not the kind of cover that the player has been afforded recently. Whatís more, the player may not yet have figured out that the HECUs will charge right around the cover and resume shooting. (Especially for the time, this was not a common feature of AI, and the HECU troops react and move much faster than most of the units in Quake or Goldeneye.) This fact makes this set piece a skill-check, where the player is forced into a do-or-die firefight with no options for escape. Because Freeman has just come up on an elevator, there are not even any long paths to use for kiting the enemy. A stand-up fight is the only real option.

For Half-Life, this is probably the biggest challenge yet. By this I mean that the game hasnít exposed Freeman to enemy fire like this before. Up until this point, the player has faced the following:

- High-damage enemies, but with copious cover available (turrets, marines)

- Medium-damage enemies that appear suddenly, but move very slowly (zombies)

- Low damage enemies that move quickly (headcrabs)

- Platforming and puzzles

So the playerís ability to handle this sudden level of exposure is probably dependent on their exposure to other FPS games in which such scenarios were common. Players of Quake and Doom might actually feel more comfortable with this fight than all the cover-intensive situations that came before it. Circle strafing while taking large amounts of damage was, up until the release Half-Life, the norm. But purely within the context of Half-Life, this set piece serves as a wake-up call or spot check.

SET PIECE 8-6: Conflict of Interest

For this set piece, Iíll assume that the player does activate the trip-lasers in the tunnel that begins the battle. This will activate the two turrets located on either side of the cart track.

The set piece is fairly obvious; there are firing enemies in every quadrant, and Freeman can end up as the target for all of them. Despite being obvious, this setup is very strange. Chapter 8 is dominated by the cover theme, but thereís definitely an arena dynamic to this room. Thereís no real cover, except for the wide aperture of the cart tunnel, so the player has to stop the cart completely in order to not get shot from every quadrant. Because the turrets and Bullsquids can choose any target, the action of this set piece can vary greatly, and killing the enemies in any one quadrant will greatly affect the overall flow of the set piece from that point onward, just as we will see in the arena set pieces later in chapter 11 and onward.

SET PIECE 11-1: Patrol

This short set piece serves as a kind of reintroduction to the arena theme, which has been dormant for the past few chapters. There's effectively no cover, although the player can, to some degree, cut the four marines into two groups that fire separately.

The crucial difference between this setup and those in chapter 8 is the lack of station-to-station cover. The player can hide Freeman around a corner, but the marines start charging as soon as they see Freeman, and there's nowhere to flee except down a long, exposed hallway. The player can use the lip of an aperture as cover, but the apertures are so wide that charging marines can surround and pummel him with fire. This is a great example of Half-Life showing its Quake lineage, as set pieces that might have been methodically dissected by a player dashing from cover-to-cover are instead turned into fast-paced brawls. Here, precision shooting and evasive movement (run-and-gun tactics) return from the past to show their usefulness in Half-Life.

SET PIECE 11-2: Four Pillars

Although the arena hasnít yet become common in Half-Life by this point in the game, set piece 11-1 disguises (or combines) its first arena as a puzzle. Freeman enters the arena via a large and normal door, with no enemies nearby. The room is filled with laser-mines, which are configured as a minor puzzle.

Because of the emptiness and spaciousness of the room, itís tempting to simply shoot the mines and obviate the jumping puzzle. This is a typical Half-Life deception, however, as the detonation queues an attack from both marines and alien grunts.

The arena itself is probably the most Doom-like example of level design in the entire game. In Doom, a monster closet would open at this point and drop enemies all around the player character, forming a shapeless melee with no clear direction or order. In Half-Life, the players will note that there are three ingress points on two sides of the arena, and will be able to apply some of their own structure by using the pillars. In 1998, it was pretty likely that experienced FPS players would have stayed in the arena and fought it out with the grunts and marines. Thatís what previous FPS games tended to be about, and itís certainly a viable option here. Half-Life gives the player a thoughtful alternative to a straight up brawl, though, and in doing so (here and many other places) I think that it inaugurates a strain of new FPS designs typified by Deus Ex. (Obviously Half-Life came first, but we tend to see Deus Ex as the exemplar of this kind of set piece because it uses them so often, whereas Half-Lifeís focus is elsewhere.) In this strain of FPS game, there is almost always an alternative to direct confrontationóan alternative not immediately apparent to players who rush in. This alternative is frequently more rewarding and less exhausting (in terms of HP and ammo) than direct combat, although it may take away from much of the run-and-gun thrill of the game. Itís always important that the designer finds a way to ďspeakĒ to the player about these situations, thoughóto tell the player that the alternative is intentionally designed into the game and ought to be pursued. The three ingress points of the enemies start the process, but the dead marine lying at the end of the back hallway is the real key. Beside him are three mines, and beyond him is an overlook.

This setup tells players who run into this alcove exactly what to do; even if they have to figure it out very quickly, itís easy to sense the ďsuggestionĒ that the player use the mines and bait the enemies to come charging into them. This kind of communication between designer and player is pretty common in the game as a whole, but I think this is one of the more elegant examples of it.

SET PIECE 12-10: Drop Zone

Chapter 12 gives us the purest arena challenges in the game. This challenge sends three alien grunts rushing out of a door to challenge Freeman. At the same time, a dropship swoops overhead and starts sending down pairs of marines into the fight periodically. Because there isn't really anywhere to hide, this set piece can get very chaotic, but thatís good thing.

The real and present potential for failure is an important part of action games. Indeed, the right kind of failure can make a game more fun, rather than less. This set piece manages to be pretty fun while also being deadly, and so we can glean some lessons from it. I'm going to list some characteristics of this set piece and how it kills Freeman when he doesn't succeed.

- The battle lasts a long time

- Death doesn't happen suddenly

- The battle changes every few seconds because of new marines dropping in

- The AI reacts dynamically, meaning every battle is different

The first two items are important because they mean that each attempt lasts for several minutes. In some cases, this can be a horrible thing; for example SNES and Genesis games tend to have problems with long encounters, for example. Long boss battles, especially those from the 2D era, were often brutal attrition matches that quickly wore out the player's patience. The reason players lost patience was that the boss battle proceeded in the exact same way through every death and repeat, and so the battle quickly grew boring. Moreover, in those battles, it often was the case that the player would lose a life because of one or two ďlast ditchĒ attacks right before the boss died. This meant endless repetition followed by sudden defeat which is not just exhausting but humiliating too. This brings up the second point: in this set piece, death doesn't happen too quickly. Freeman has to take sustained damage from several enemies to actually bring him down, and while that's likely in this set piece, it isn't fast and it isn't certain.

Because the battle will play out for longer than just one horrible moment, each experience of the battle will be different because of the latter two items on the list above. Obviously, the periodic appearance of two more marines will update the battle on a regular schedule. The marines arrive at the same interval over and over again, though, so they're not the principal cause of the dynamism in the fight; they're just a way of keeping that dynamism going. The real reason why the set piece is fresh on each play-through is the AI. The AI of each unit involved in the battle is autonomous and reactive, and as such, no two battles will go the same way. So all of the other thingsóthe length of the battle, the relative survivability despite the total lack of cover, the constantly dropping marinesóthese things are all in place to support the dynamic AI which will make every play-through of this battle different. That's why it's okay if the player has to retry this battle several times; each time will feel fresh. And it doesn't even require specially programmed AI; it's just the standard AI that exists for these units all of the time. Good encounter design takes full advantage of the resources at its disposal, and this is a shining example of that.

SET PIECE 12-13: Upon a Catwalk

This set piece derives its dynamic quality almost entirely from the composition of the enemies. Although there is a catwalk, and it is useful, the set piece becomes really dangerous if either the marines or the aliens who are fighting below get a clear upper hand. The aliens have an advantage at the beginning.

Even with the entrance of more marines via the APC, the grunts are too beefy and put out too much damage for the marines to handle them without cover and explosive munitions. Moreover, the placement of the marines seems to activate their movement jitter in a way that affects them adversely. While the player obviously has no stake in the battle per se, it behooves the player to take advantage of the distraction very quickly to get some shots in before either side is targeting Freeman. Failing to hurry means taking a lot more damage, because even the catwalks donít serve as good cover for those heat-seeking grunt bullets. The only real problem I have with this set piece is that itís impossible to know how the arena dynamic will play out before entering the room, and there arenít many encounters like this one later in the gameói.e., thereís no time to learn the most obvious lesson this set piece teaches. That said, the increased speed of this arena and the next one help to train the player for their much more chaotic encounters in Xen, even if none of those later arenas have enemy infighting.

SET PIECE 13-4: Upon a Tank

This two-part set piece is quite similar to the last one in terms of enemy composition, and indeed shows some classical evolutions. The initial layout is the same, with Freeman entering from above on a catwalk. This catwalk is shorter and even more exposed than the last one, but it serves well enough as a platform from which to snipe a few enemies at the beginning of the fight. The big evolution comes when the player uses the tank to blow a hole in the far door after killing the initial group of enemies. Immediately after that, enemies start arriving by teleport in staggered waves and varying locations.

Either because of the shape of the arena or because of some unique AI script, these enemies charge extremely aggressively if Freeman hides behind anything. Some cover is present, but itís totally useless. Instead, the player is apparently meant to use the machinegun on top of the tank to quickly eliminate these aggressive enemies, much like in set piece 12-12. The position on top of the tank does leave Freeman exposed, but the only other option is to run through the objects in the arena and waste a lot of ammo taking out the grunt. While arenas are made for movement, and the architecture here suggests it would be possible, this is unusually difficult. The lack of a third faction to draw some fire, combined with the unusually aggressive movements of the enemy aliens, makes the typical run-and-gun strategy inappropriate.

SET PIECE 14-5: High/Low Grunts

This is the first of three set pieces which deal with the same basic layout in different ways. The idea being iterated is a donut-shaped arena with three grunts placed in it. The arena is quite small, and so putting three alien grunts in the arena means packing a lot of damage into a small space. In this first iteration, all of the grunts are on one side and out of view. The approach to the room may telegraph the fact that there are enemies in it, but I doubt many first-time players are expecting the barrage that they get.

The aggressive movements of the grunts and their ability to fire homing bullets mean that Freeman is going to take a lot of damage very quickly. As before, each individual bullet doesnít do that much damage, but because the grunts have so much HP, theyíre going to keep firing for a while. In set piece 12-8, the presence of three grunts was mitigated by the presence of the HECU marines who distracted them. In this set piece, thereís no such distraction; itís just Freeman and the grunts.

The only consolation is that it is possible to use the walls and catwalks for very slight cover, for one or two seconds. The approach to this set piece isnít really an aperture as much as it is an entire hallway, but the wall and narrow walkway can be used to avoid taking damage from all three grunts at once. The corner also works as a decent chokepoint for explosive munitions or automatic fire, but thatís still not really cover in the sense of the term that the game has been developing. Itís only a very slight reprieve from one third of the encounter.

Similarly, the player can play cat-and-mouse from below the catwalk with the final, elevated grunt. The whole set piece, and the catwalk section in particular, are strongly reminiscent of Quake and Quake 2. Some of Quakeís most idiosyncratic moments in multiplayer come when players are shooting up or down through catwalks at each other; this set piece definitely recaptures the speed and intensity of that kind of encounter.

SET PIECE 14-7: Evolution of High/Low Grunts

This is another iteration of the idea of three grunts in a room. Itís also one of the clearest examples of how the CCST structure can be applied to Half-Life. In this case, the same type of room (donut arena with a catwalk) is now filled with more enemies and a different encounter design. Technically, this room is an evolution because it introduces a new type of enemy, instead of increasing the number of enemies already established in 14-5.

The two grunts on the ground are more or less the same, although this time around the barnacle tongues can interfere with maneuvering around the narrow walkway of the donut arena. Once again, there no meaningful cover, there are only one-use chokepoints that will lose their utility if the enemy isnít dispatched quickly. The third grunt appears once the player ascends the catwalk, dropping almost on top of the player, and then down to the floor below.

This time around the player has the height advantage, but true to Quake form, itís not really an advantage. It is a qualitative change, however, and along with the addition of barnacles itís clear that this set piece is what we call an example of an A+B evolution. In an A+B evolution, new elements are overlaid on the original idea. Itís probably the simplest kind of evolution to see, and thatís most of whatís going on here. The only real twist is the delayed arrival of the third grunt, which would fall more into the category of a mutation (qualitative change without increased difficulty) if it werenít accompanied by the rest of the evolutions in the set piece.

SET PIECE 14-8: Aux Tank Room

The Aux Tank Room is another iteration of same donut arena idea, although this time the verticality has been removed. Nevertheless, this is an expansion/evolution of set piece 14-5. Because it does something different than the other evolution (14-7), we ought to call it a ďsiblingĒ evolution, since it has the same parent as the set piece we just discussed. Both set pieces have the same base idea, but their deviations go in different directions from the same starting point. The defining feature of this arena is the teleportation of two (and sometimes, later, two more) alien grunts behind Freeman.

Once the player defeats the first two grunts and passes more than halfway into the room, two more grunts will teleport in after a slight delay. The really remarkable thing about this is that while we have seen dozens of teleport-driven monster closets in this game, most of them have occurred to start a set piece. Moreover, most of them have been in the cover theme, where the player's reaction can be to take advantage of cover so as to mitigate the threat of new enemies. There isn't much to hide behind in this set piece, and even less once Freeman advances out of the room's aperture. So when those grunts appear, it's one of the most immediate threats in the whole game, at least outside of boss fights. The player is going to have to do a lot of running and gunning, and fire the highest-powered weapons. The whole arena theme owes a lot to its Doom and Quake heritage, but this set piece stands out in that regard even more.

SET PIECE 14-12: Last Call

This set piece is a study in how a good design practice can be overemployed. Climactic set pieces like this one can be problematic when the designer forces the player to do something that they've never had to do before. They can also be anticlimactic when the player has to simply reiterate the same old process all over again. Neither of these is a reliably good option (although there are exceptional cases). One strategy that a game can employ when trying to create a climactic set piece like this one is to implement a "next intuitive step" in design trends. A goodóbut anachronisticóexample of this is the boss battle in Portal. In that game, the player has spent the entire game building up the skills to open portals while already falling, or while an object is already falling. The final fight inverts that to some degree; instead of opening portals to fall through, the player is opening portals for the boss's missiles to fly through. The change from falling objects to flying missiles is significant, but it's also completely intuitive. The player is going to miss a few early shots, but all the skills that he or she has built up over the course of the game will translate perfectly to the new task with only a little practice. The new task depends on the same old mechanics to be familiar, but it changes just enough to be fresh.

The problem with the last set piece of chapter 14 is that it makes the same kind of change seen in Portal, but it does it to a greater degree and in too many ways. Firstly, this is an example of arena combat, but it's also a step forward in architecture. The pillars at the center of this arena give the it shape and dynamismóbut only for Freeman. The alien overseers who come out are floating above the architecture, giving them an unfair advantage.

This one change is fine by itself; the game should be harder at some points than others, and this set piece isn't impossible by any stretch. This set piece and its architecture even prefigure the fight with Nihilanth rather well. There's still more going on, though. The second problem is the escort quest that occurs in this set piece. The player has to protect the scientist who is opening the portal. This is not the first time the player has had to protect an NPC, but the leap in difficulty is quite large from the last time this happened and from any of the set pieces in this chapter. The NPC has been moved away from Freeman and is much more vulnerable than Freeman himself is. Also, this set piece introduces a new enemy type never seen before.

Introducing a new enemy type is a totally orthodox thing to do in any game, even if the player hasn't been at all prepared for the behavior of that enemy. In Half-Life, the player has had some recent experience shooting up at grunts on catwalks, and has been shooting at marines in high positions for most of the game. The alien overseers are smaller and faster than those earlier enemies, but the player knows the appropriate mechanics for dealing with them. If it weren't for the presence of the escort quest, the unlimited number of enemies, the long range at which this combat takes place and the change in arena architectureóif not for all of that, the overseers would be a totally fair challenge.

Each of the evolutions listed above are completely orthodox, tried-and-true design practices. The fact that all of those evolutions are suddenly introduced at once in a very high-stakes situation makes it unfair to the player. If each change had been introduced, and then had been combined after their introduction (in an A+B+C evolution), the player would feel more prepared for them. Considering that Valve usually does such a good job of incrementally increasing the complexity of their set pieces in this game and their later titles, it's strange that they would fail to do so here. Properly preparing a player through incremented introductions doesn't make set pieces any more boring, because each progressive evolution is still more complex and (usually) more interesting. Implementing those evolutions one by one simply makes the process fair.

SET PIECE 16-1: Gonarch

The Gonarch battle is essentially a three-arena fight, each arena smaller than the last. That in itself is very simple, but itís the behavior of the Gonarch that makes the fightís design interesting. The behavior of the Gonarch changes in a way that recalls the bosses of early-90s 2D shooters. In the days of the scrolling 2D shooter, boss fights tended to be highly mobile, with all the motion of the fight being dictated by the boss rather than the player. The movement patterns and firing patterns of those bosses also changed across phases. The fight against Gonarch is one of the best early examples of the same thing taking place in a 3D shooter. All of the iD games were replete with boss fights, but they tended to lack phases and the player often dictated the movement of the battle. That is to say, in 2D scrolling shooters, the boss acted (by executing a predetermined pattern), and the player merely reacted. In 3D shooters until Half-Life, the player acted, and the boss reacted by simply tracking the player through 3D space. Although Gonarch doesnít follow the same kind of exactly choreographed pattern that its 2D ancestors did, it does have a cycle in all three encounters. The Gonarch will alternate a charging behavior that heads right for the player with a stationary activity that involves shooting acid and spawning enemies. Itís a very simple pattern, but what enriches it is the Gonarchís discretion in its ability to charge. When charging, the Gonarch targets Freeman wherever he is standing, and the charge will terminate in a variable amount of time depending on the distance between Freeman and the monster during the targeting phase. The combination of a predetermined pattern plus some variability gives this fight the best aspects of both its 2D and 3D ancestors.

The fight has flaws, however, and the biggest one is definitely that thereís no way to tell how much HP the Gonarch has. Most FPS titles of this era had this problem, but if the designers had already set out to recapture the best aspects of the 2D shooters, itís strange that they didnít find a way to indicate the state of the monsterís HP at all. This is more important because the Gonarch has a weak point.

The underhanging gonad (the name seems obvious now doesnít it? Arch-gonad?) is an obvious weak point, but itís not clear if the player can or canít shoot other parts of the monster for moderate damage. And itís not entirely clear that bullets affect it, either, even though they do. This is an objection I have raised elsewhere, but itís more troubling in this fight because of the monsterís very large pool of HP. Yes, the phases indicate a change, but transparency in any action game is a good thing.

Thereís not much to say about the three arenas other than to look at the relationship between them. In the first and third arenas, there is some cover. In the second arena, there is essentially no cover, and the player can fall through the floor in such a way that the fight becomes impossible to finish. To mitigate that last problem, the second phase is usually the shortest in terms of HP to deplete.

The arenas get smaller each time, making it harder to evade the Gonarch. In a truly brutal series of evolutions and expansions, the cover would disappear in the second arena and not reappear in the third. Thatís exactly the sort of thing that would have happened (and basically does happen) in Quake and Quake 2. It doesnít happen here, however. The other unique thing to happen here is that the Gonarch stays above Freeman for at least a little while. That one part of the fight is actually quite fascinating, and represents the culmination of all the verticality in the game.

Aside from firing upwards and running around to avoid the tiny crab creatures, thereís not much to this part of the fight, but the fact that the designers included a kind of capstone experience to the vertical design elements in the game is still fairly impressive.

With that out of the way, thereís an interlude to the arenas in between the first and second that features a problem endemic to boss fights. If the player doesnít race alongside the Gonarch to the second arena, the creature will charge in a very narrow space at the bend in the hall.

This will kill many inexperienced players. Once known, this attack is fairly easy to avoid, but I think this type of difficulty is an indictment rather than a credit to the design. Because the Gonarch doesnít really telegraph its charge, and the darkness of the corridor obscures everything, the player canít always see it to avoid it. The player dies once to learn that the attack is avoidable, but why is such a death necessary? I donít believe that this is a good kind of difficulty; it is, in the oldest sense of the word, artless. Avoiding the Gonarchís charge in the tunnel doesnít suddenly reveal something about the Gonarch that the player can use to defeat it during the other phases; itís simply an unnecessary bottleneck in an otherwise solidly-designed fight.

SET PIECE 17-1: In the Sky

In theory, the combination of platforming action and arena-style shooting could be great, but this isnít. I place this in the arena theme because although there is platforming, the real difficulty in this set piece is fighting the many waves of overseers without cover. Really, the awkwardness of this set piece means it doesnít belong in any organizational structure, but arena is the one that comes closest. If nothing else, this set piece shows how much of a difference there is between the arenas of Xen and the those of Black Mesa.

The big problem here isnít just the presence of overseers, but rather that the platforms are not conducive to dodging, and there is no cover. The mismatched orbits of the platforms move slowly through the sky, making it very difficult for the player to rush through them. Moreover, jumping back and forth is incredibly difficult because of those orbits and the large height differences between the platforms. Finally, the platforming mechanics of Xen are just as bad as they ever were. Presumably, this set piece exists to prepare the player for the Nihilanth fight. That fight, however, is fair and gives the player plenty of leeway. This fight is a series of tiny aerial arenas, and the whole point of the arena theme is mobilityóbut the player doesnít have that here. Itís really a shame because the combination of platforming and shooting works really well in the Nihilanth fight, but itís poorly implemented here.

SET PIECE 17-3: Two Guardians

This set piece is an arena version of an earlier cover set piece, 12-4. I like this set piece as an example of the convergence of arena and cover design, where ideas from both themes come together. There are two geological formations that obscure the playerís view of two alien grunts. Like set piece 12-4, the enemies here can surround Freeman no matter how he approaches the set piece, if the player is not careful.

Unlike the previous set piece, there isnít anything here that can work as reliable cover. The two mounds are a kind of downgraded version of the boulder that existed in 12-4. They might grant an instantís reprieve from grunt fire, but their only real purpose is to give the arena shape and hide the second grunt. Itís sometimes possible to isolate one of the grunts for a moment, but that grunt will always be able to fire back at Freeman with his homing bullets. This is as close as the arena and cover themes can probably come together in the context of Half-Life (depending on how you view the Nihilanth fight). As weíll see in the next few set pieces, the cover and arena themes have some serious conflicts when their design ideas overlap.

SET PIECES 17-6 THROUGH 17-9

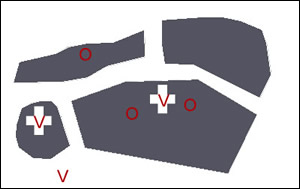

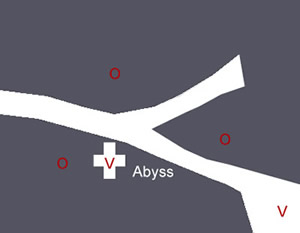

These set pieces represent variations on a common theme which don't make much sense in the context of Half-Life's level design, but which would be totally at home in a Quake game. Each of these three set pieces follows the same essential formula: there is an arena-type set piece with a large pit in the middle. In chapter 14 we saw several set pieces along these lines in the three grunt rooms (14-5, 14-6, 14-8), but the idea here has become a bit bloated. The set pieces are extremely large, at least double and in the case of 17-6, probably three or four times the size of their ancestors in chapter 14.

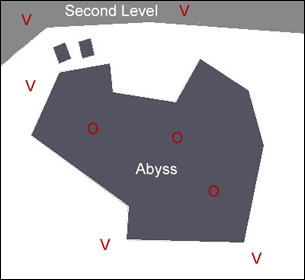

O = Overseer; V = Vortigaunt

The central challenge of each set piece is the alien overseers which hover over the central pit. I like this as an appropriate use of the alien overseerís flying abilities, and it works as a next-level challenge for the player's shooting abilities, but where are those things supposed to fit in the greater context of Half-Life? In the Black Mesa part of the arena theme, this set piece would have been about mobility and quick reactions, but here, the huge size of these set pieces, the terribly small walkways, and the gaping holes in the middle really hurt the playerís mobility. Moreover, because of the arena size, the enemies are farther away than normal.

In 17-6, the Vortigaunts along the perimeter can be hard to hit. Half-Life has rarely demanded long-range combat before, and definitely never at a sustained distance like this. The weapon loadout offered to the player isn't really up to the task. There is no sniper rifle, and the nearest weapon (the crossbow) has slow-moving shots that are not ideal for this range. It's not impossible to hit the enemies with the magnum, for example, but it's difficult in a way that the game hasn't prepared the player for.

It's easy to see how the set pieces relate to one another, at least. Both of the later iterations of 17-6 contract the size of the arena in a meaningful way and add something new. First, 17-4 adds some perimeter cover, but again thatís rather out of place in the context of the larger game.

What is the player supposed to do with this cover except wait for the alien overseers to get in a good position? There's no direction or implication in the cover; it's almost as if the game has reverted all the way back to the kind of dynamic found in Space Invaders. This would be pretty funny, since Freeman is fighting actual space invaders, but the long range and unclear dynamics of the set piece are unlike the smaller, purposeful set pieces that make up the majority of the game's content. There's too much waiting and sniping while in cover, so it feels like a different game from the tight, tense action of chapters three to fourteen. Set piece 14-8, meanwhile, has a very interesting evolution in the way it puts Freeman in the middle of the arena, surrounded by two large pits.

Putting the alien overseers on either side of Freeman as he crosses the bridge is a clever way to turn the iterated idea on its head, but that doesn't necessarily excuse it from being unlike everything else in Half-Life. Thereís no cover and very little ground to run on, so the arenaís best resourceómovementóis diminished terribly. The designers seem to be trying to give the game a sense of climactic grandeur, and the look of the levels certainly accomplishes that. Riding up all those elevators to the giant, hovering teleport pad does create a palpable sense of a coming climaxóit's just a shame that the game design doesn't really follow suit.

SET PIECE 18-1: Nihilanth

I normally do not say much about a gameís boss fights when writing a Reverse Design. I am even more hesitant to write about the last boss fight of a game because designers tend to do one of two things that make writing about these fights somewhat pointless. The first option is that designers adhere unswervingly to design trends theyíve already established in the game, and simply make the boss fights a sustained, slightly more difficult version of whatís already been done. I have no objection to this in principle; I think it makes for good games and good boss fights. Sometimes thereís just not much to say about such a fight that isnít better illustrated elsewhere in the game. I do object to this when the last boss fight is padded with pure, unexciting reiteration, although that is not the case here. On the other hand, the last boss fight of a game is frequently very different from the rest of the game. I do object to this, as it is bad game design. If you, as a designer, are going to spend a whole game teaching a player how to do activity X, why would you want them to do activity Y at the last minute? The best example I can think of is the boss battles in Super Mario 64, which depend on a mechanic not used anywhere else at all to deliver the killing blow. Half-Life, interestingly, sits halfway in the middle of these two poles.

There are two phases to the battle against Nihilanth, and the first one is full of redundant errands. Nihilanthís arena itself is actually quite standard for the arena theme. The player can hide behind pillars, but it isnít exactly cover. For most of the fight, he canít fire from cover to deplete enemy HP. For part of the middle phase, Freeman can actually use cover, but the rest of the time, itís an arena encounter. The player spends most of the time behind the pillars waiting for Nihilanth to make the first move. This is somewhat disappointing, because the game is mostly about cover dynamics.

The teleportation attack is not clearly explained in the game design. Colorblind players and anyone who doesnít put the color pattern together naturally will spend a long time learning not to dodge, assuming that they ever figure it out. The Nihilanth does not move, however, and this is actually somewhat refreshing, as firing into the sky at moving targets has been an unfair and largely un-fun task for enough time already in Xen. The real problem is the layout of the rooms the player is teleported into. I wonít get into each roomís particulars, because they are essentially all just lifted from other parts of the game, but there is one room that stands out in its odiousness. The very tall platform chamber is not only far too large, but it is also far too difficult in the dimension where Xen is the weakest.

I would estimate (after writing an entire book about it) that more than 95% of the gameís content is either shooter content or normal-gravity platforming content. So asking the player to make a series of difficult jumps for which they have not been preparedówhen all they want to do is kill the last bossóborders on mockery. I credit the design team for not using fall damage to make it even more frustrating, but this section is just entirely out of place. The developers have done such a good job of putting platformer content in the game to break up tension, but who wants to break the tension of a last boss fight?

The two phases of actual combat against the Nihilanth itself are much more in line with the rest of the game than the teleport-rooms. The first phase in particular is almost entirely orthodox arena content, and where it deviates from the norm it does so in keeping with the spirit of the design. Although the pillars arenít really cover, theyíre quite useful in the way that architecture in the arena theme sometimes is, since the player can successfully hide and still see the creature. Freeman isnít fighting from cover in the first phaseóheís running between blastsóbut at least the designers have made it possible to do so without taking splash damage.

The other big improvement is that the boss takes visible damage; in the second phase, the bossís energy orbs disappear and ichor leaks from his skin when shot. All of the big enemies of the game, the Gargantua, Helicopter, Ichythyosaur, even the Gonarchóthey donít telegraph their remaining HP the way that the Nihilanth does. Sometimes itís hard to even tell that Freemanís shots have hit those enemies in a vulnerable area. The reason itís different this time is probably that if the creatureís HP amounts werenít visible, the puzzle involving the healing crystals would be completely indecipherable. I donít know in what order the set pieces of this game were designed, but it seems strange that after designing this fight, the designers didnít go back and add some semblance of HP indicators to other bosses. Nevertheless, the bossís HP and related puzzle are both easily understood, and thatís a good thing.

The final phase of the fight isnít quite as clear as the first phase, in that it asks the player to do something new. This new task is defensible because the designers have spent at least some time preparing the player to do it. The second phase involves jumping over the Nihilanth and firing down into its brain case. On its surface, this is entirely within the realm of skills taught to the player already. The player has done plenty of jumping, and even done quite a bit of jumping in Xen gravity by now. Iíve already raised my objection to the Xen platforming mechanics, and that objection stands. As far as jumps in Xen go, however, this is a relatively fair one. The jump over Nihilanthís head is combined with a downwards-facing shot. Up until this fight, there has never been an instance where the player had to fire and jump at the same time. There have been plenty of jumps and a fair number of instances of firing downward, however. With that in mind, this is exactly the kind of A+B evolution that designers had been implementing in videogames for years before Half-Life came out. I would have liked to see some combination of jumping and shooting before this to really prepare the player, but at least the player has used all the component mechanics before.

The Platform Theme - Back | Next - Non-Theme & Through Content